We love the outdoors but hate getting wet. From rain and sweat. The solution is waterproof and breathable rainwear. But how does this work?

For everyone who likes to go outside, it is important that you can protect yourself well against wind, rain and snow. For that protection we resort often to waterproof and breathable materials. In this article – and the accompanying tutorial video – I’ll explain how it is possible that a waterproof material breathes, what type of breathable fabrics there are and why breathable waterproof fabrics are not always a blessing. But first why do we need waterproof and breathable rainwear?

There are two main reasons why we need waterproof and breathable rainwear. The first being that we generally don’t like getting soaked up to our undies on our hikes, backpacking trips or biking adventures. The second reason is that staying is staying comfortabel. Staying comfortable means that we need to get rid of the sweat that we produce when we are being active. And… staying dry also results in staying warm and thus saving energy.

Blast from the past

An article about waterproof and breathable rainwear is not complete without delving into my history of waterproof clothing. If you are over fifty, like I am, you probably remember how you used to bike to school in bad weather: in a rain jacket and rain pants. Both very windproof and waterproof, from the outside but also from the inside. Sweat had nowhere to go, so you and I ended up soaking wet – and smelly – at school. That changed in 1969.

W.L. Gore & Associates

W.L. Gore & Associates have been developing PTFE, or PolyTetraFluorEthene, since 1958. Both owners – Vieve and Bill Gore – initially used PTFE to insulate electronic components. Nowadays we mainly know the brand name: Teflon, the non-stick coating in our pots and pans.

It was the son of Vieve and Bill – Robert (Bob) Gore – who discovered in 1969 that PTFE could also be stretched into a foil. He discovered that this foil is micro-porous, and this started a true revolution in the world of waterproof clothing. You will have noticed by now: we call this foil Gore-Tex, and you will find it in clothing, gloves and shoes. All gear that we use and where for our comfort sweat has to go out and water must not to go in. But how is this possible?

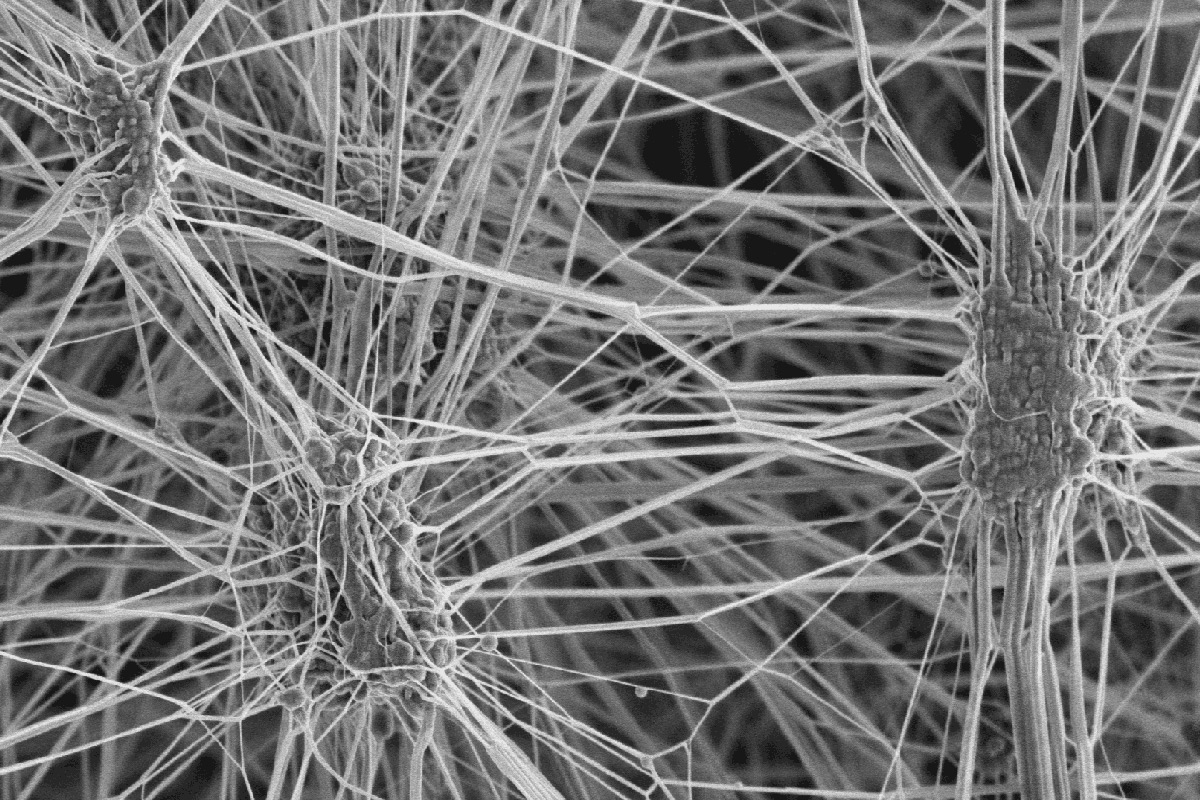

Breathable waterproof: Micro-porous

PTFE is micro-porous. Micro-porous means that there are tiny holes in the material. Those holes are so small that water vapor can pass through the material, but water droplets cannot. Sweat is water vapor and can therefore pass the fabric but the larger raindrops can’t. In short, breathable and waterproof and for completeness: also windproof. This also applies to all other materials in this story. We usually call such a breathable waterproof micro-porous layer a membrane. And… fun fact: You carry the most famous membrane with you every day: your skin!

Breathable waterproof: Hydrophilic

The best known – or most commonly used – technique to make a material breathable and waterproof is a micro-porous membrane. But there is a second method: the hydrophilic method. In the hydrophilic method, the material itself has the property of transporting water molecules through the material. Compare it like a chain of firefighters passing a bucket of water from the ditch to the house on fire.

Membrane versus coating

To complete the above story, we still have to talk about the processing of these micro-porous or hydrophilic materials in our clothing. We have two flavors: as a coating or as a membrane. We speak of a membrane if the micro-porous or hydrophilic layer is a film between the lining and the outer fabric. Or if it is bonded to the outer layer. In the case of a hydrophilic coating, it is applied as a spreadable layer on a support. This is usually the inside of the outer fabric.

2-, 2.5 and 3 layers

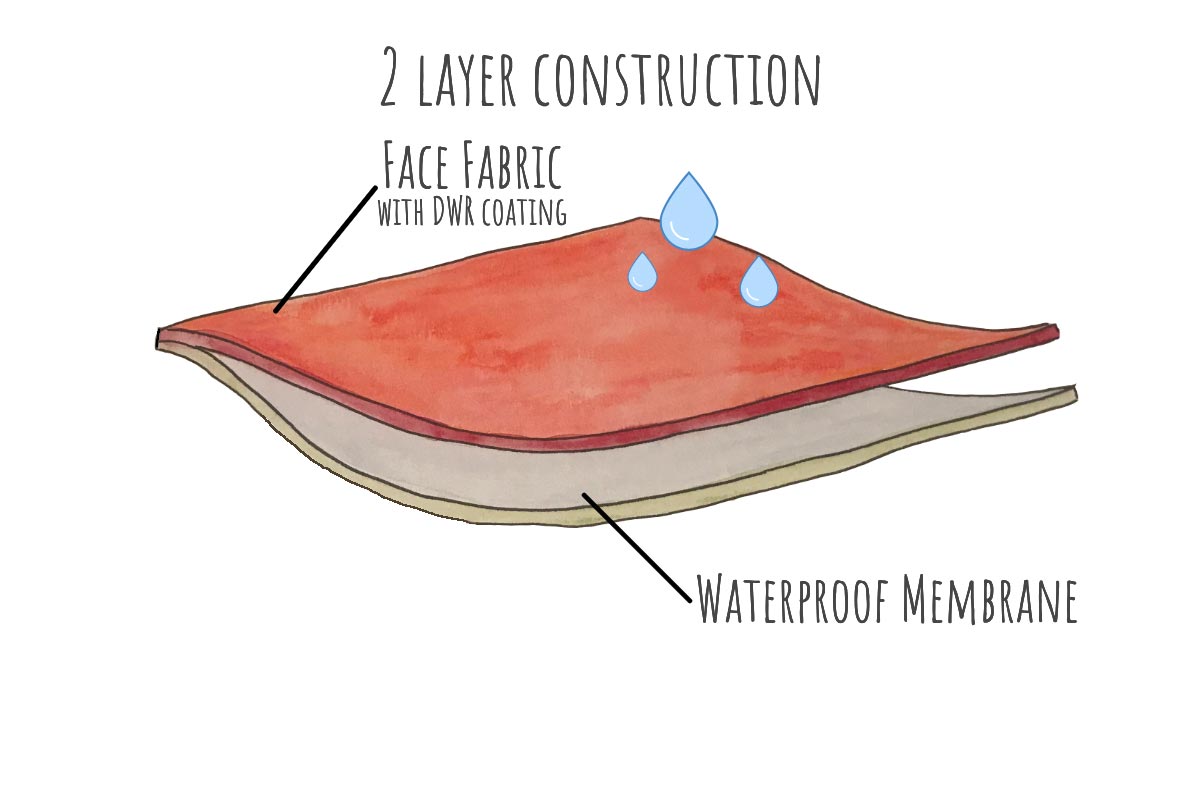

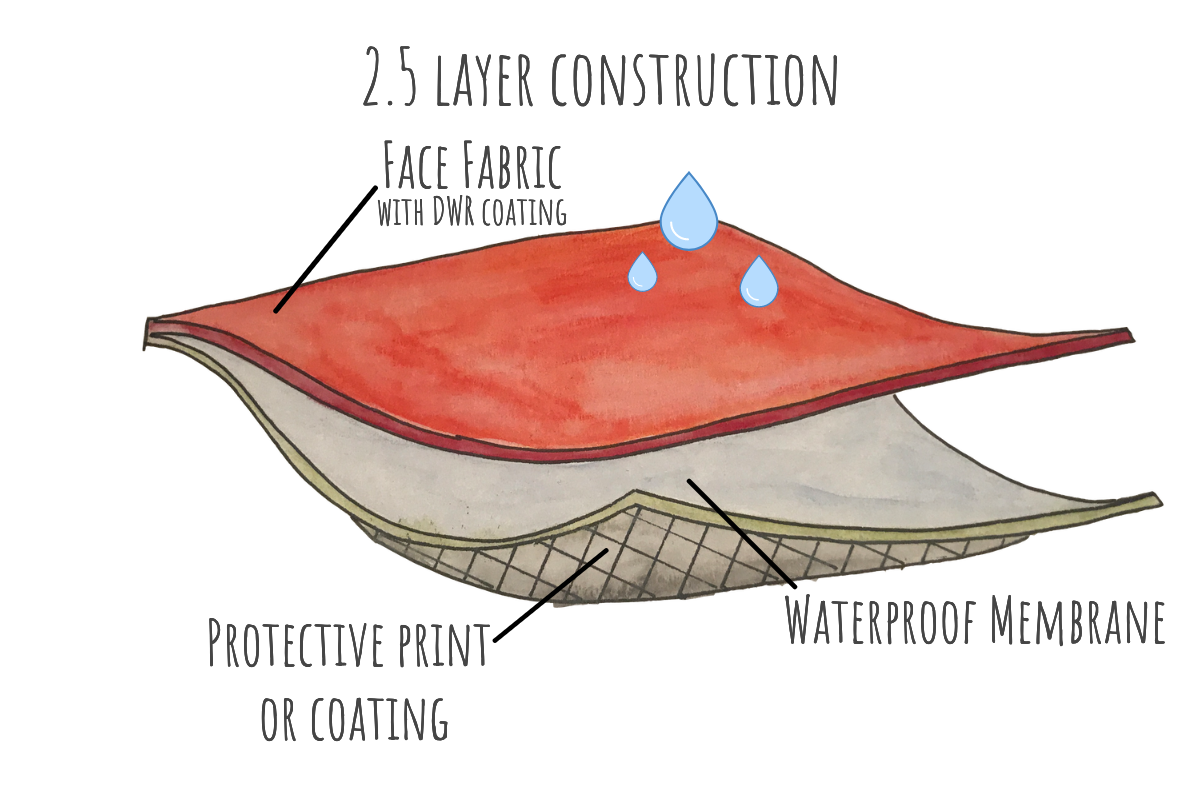

Although PTFE – or other membranes and coatings – is very strong, it is most of the time connected to an outer fabric for abrasion resistance and weather protection. On the inside the membrane or coating have an inner layer to protect it from body oils and to make it abrasion resistant from the inside. Now this sounds a lot like a 3-layer and still… it is not automatically a 3-layer laminate. Let’s have a closer look at 2-, 2.5 and 3 layers that our waterproof and breathable rainwear is made with.

2-layer

When the membrane or coating is bonded to the inside of the abrasion resistant outer fabric, we generally speak of a 2-layer laminate. To protect the skin side of the membrane or coating a loose-hinging liner is often used. Because of this construction most of these garments are a bit bulky but comfortable and most of the time price wise a bit cheaper.

2.5-layer

We generally speak of a 2.5 layer if the laminate or coating is connected to an outer fabric – like in 2-layer and 3-layer systems – and there is a thin coating or print on the skin side of the membrane or coating to protect it. The 2.5-layer construction gives us garments that are light, very packable and price wise more affordable. The downside of many 2.5-layer jackets is (or was) the next to skin feel; some feel very sticky. This is changing with new materials that do feel nice on the skin.

3-layer

With a 3-layer laminate, the membrane is processed as the white layer of an Oreo biscuit between an outer and an inner fabric. This is the most robust method and the method that you will find for example in jackets that are used in combination with a heavy backpack. A result of this construction is most of the time bullet proof rain jackets with a reasonable pack volume and a higher price. And they will last a long time.

Although the above is in general how membranes and coatings are incorporated in a layer-system, there are always exceptions and variations; it’s not black and white in the layering world.

PTFE and sustainability

PTFE membranes – with Gore-Tex as the largest and best-known manufacturer – and the products they contain have the reputation of being environmentally unfriendly. Some nuance is in order here, because quite a few experts have come back a bit. There are several reasons for this.

A membrane made from PTFE has proven to be a very durable material. The outside material usually wears out faster than the membrane itself. In addition, PTFE is a material that reacts with nothing; it is inert. This makes it not immediately environmentally friendly, but also not unfriendly; it never ends up in connections with organisms as is the case with microplastics. That is also the reason why PTFE is used for, for example, artificial blood vessels and water purification plants.

In principle, Gore-Tex can be recycled as a material and Gore has had programs for this in the past. Unfortunately, Gore canceled them because we did not return our garments. And of course, it is difficult to separate the construction of outer fabric and Gore-Tex membrane. If a jacket is at the end of its lifespan, it can at most be used as a material for another less high-end product – from jacket to bag – or dumped or burned. The latter is really the better choice, because it does not produce harmful waste.

Gore claims they are busy looking for more environmentally friendly alternatives to the PTFE membrane. However, it is not that far yet because they cannot yet guarantee a long lifespan like the Gore-Tex membrane. Others – such as Dermizax, SympaTex, Pertex and Vaude – make breathable waterproof materials that are 100% recyclable. So you have a choice if you are planning to buy new waterproof and breathable rainwear.

Durable Water Repellent (DWR)

For breathability it is also important that the outside of a breathable, yet waterproof jacket remains as dry as possible for as long as possible. If the outer layer becomes saturated with moisture, the breathable material cannot do its job. The Durable Water Repellent (DWR) finish (or coating) has been developed to achieve this.

With a good DWR coating you can see raindrops bead up and roll off the fabric. The better the water that hits the fabric bead up and rolls off, the drier the fabric stays and the better the micro-porous or hydrophilic material can do its job. The reason why a DWR can do this job is because the DWR coating is made of peaks that are very close together leaving no space for raindrops to spread out. What happens is that several raindrops end up in the same place, they form bigger droplets that beat up and roll off the fabric thanks to gravity.

During its life, for example with a rain jacket, the DWR coating suffers from wear and tear. Also washing your jacket wears the DWR finish down. Imagine this as the peaks getting more stump enabling the raindrops to spread and saturating the fabric: the breathable material functions less. When you notice that the DWR starts to wear out – darker spots and no beading up of water – than it’s TLC time. That is another article that I have not yet finished but will follow soon.

DWR sustainability issues

Now there are a few things you should know about DWR coatings and it has to do with sustainability. Most DWR coatings or finishes contain Perfluorocarbon (PFC). PFCs are particularly harmful to the environment. The top dog is the C8 carbon chain, but this one is hardly used anymore. Slowly phased out from our clothing is the C6 chain. It is replaced for the less harmful C4 chain or even by completely different types of DWR coatings, many of which are completely environmentally responsible.

Remains the question: why are DWR coatings not completely replaced by more environmentally friendly DWRs? Well… C6 carbon chains are extremely strong and hard wearing. This is something I cannot always say about the environmentally friendly variants. They wear down faster so you will have to treat your clothing more often with a water-repellent impregnation and as long as this one is also sustainable; I don’t see any problem.

Breathable and waterproof limitations

Do breathable yet waterproof constructions always work? No, certainly not, both the micro-porous and hydrophilic methods only do their jobs under certain conditions.

Temperature limitations

In both cases it is important that the outside temperature is lower than the temperature on the inside of the material. Otherwise, no transport of water molecules takes place.

Humidity limitations

In addition, the hydrophilic method requires it to be more humid on the inside than on the outside because water molecules move in that direction where temperature and humidity are lowest.

The above also immediately indicates the limits of what breathable waterproof materials can do and that has a lot to do with weather types.

Weather types

We can skip dry warm weather: you will be nuts to walk in a rain jacket then. In warm weather and a chance of a shower, a super light, packable just waterproof jacket in your backpack would do fine. Or an umbrella of course!

A breathable waterproof material performs optimally in rainy and windy weather with lower temperatures. Then the difference between the inside and outside is large enough for membranes and hydrophilic materials to function.

The wind factor in relation to temperature is very important here. More wind means more evaporation on the outside and therefore better breathability. A lower temperature also means that you sweat less with the same effort. Result: less moisture that has to go outside. Also remember that we all sweat differently and the breathability of a jacket can vary from person to person.

Most importantly, if the outer material becomes saturated with moisture, the system will no longer work. Micro-porous materials can no longer breathe and the hydrophilic materials can no longer pass on water molecules. Then it is a matter of biting through.

Physical barriers

Above I talked mainly about the weather and body influences on the breathability of a material. However, there are still a few other physical obstacles.

First, what do you wear under your breathable waterproof layer? There is such a thing as the 3-layer system, and it is essential for materials to ‘breathe’ properly.

In short: the baselayer – the layer that is on the skin – must pull sweat away from the body. On the baselayer goes a midlayer. This functions as a isolation layer but also should help transport sweat through to the shell layer; the breathable waterproof jacket that I have been talking about. If one of these layers is made of a material that retains moisture – like a cotton t-shirt – the system can’t perform at its best and you will be uncomfortable and wettish.

Second: the backpack. Especially with large trekking backpacks and climbing backpacks, the back panel or carrying system is directly against the back. Good for stability and wearing comfort, bad for the transport of sweat. And not only the back is an obstacle, also the hipbelt and shoulder straps are barriers.

Now you know how waterproof and breathable rainwear does its work. Did I leave no questions unanswered? Hell no! That is why I wrote a couple of more in-depth articles and they will be online shortly. See list below.

If you are looking for a new rain jacket or hardshell? I reviewed a couple and this is were they are: Hardshell Rain Jackets Reviews.

- The first is about ‘What is waterproof and how do we measure if a fabric is waterproof’.

- The second article is about ‘What is considered to be breathable and how is it measured?’ (work in progress)

- I also made a list of waterproof and breathable fabrics that are produced and that finds its way into our rainwear.

So if you like to keep reading: follow the links.